New Delhi: In 2022, a Dutch scientist flagged duplication of text and signs of manipulation in images presented in a 2004 research paper co-authored by one of India’s leading virologists, Nivedita Gupta. On 26 May 2022, the peer-reviewed journal, Mycopathologia, retracted the paper, though at the time, Gupta denied the accusations, reiterating that her research was path-breaking. It was one of the first in India to document the spread of Candida infections in a burn ward, she said. The national and international science community waited to see what action would be taken. A day later, Nivedita Gupta was made head of virology at the Indian Council of Medical Research.

In the two years since Elizabeth Bik— a Dutch scientist who specialises in finding published research papers with integrity issues—called out Gupta’s work, ICMR issued no statement on whether any inquiry was initiated or if action was taken against Gupta. But since then, scientific research from India has come under increased scrutiny—not from ‘foreigners’ with access to unlimited resources but a small army of academic watchdogs within the country.

By day, members of India Research Watchdog are scientists, researchers, students and data analysts at private and public institutes. By night, they are sleuths, pouring through published papers, acting on anonymous tips and sharing information on Discord—a popular instant messaging and VoIP platform. Their mission is to investigate authors of research papers who are suspected of scientific misconduct. The subject of their investigation may not be heinous crimes—but it is a question of protecting the research integrity in India.

“No hero or fairy is going to clean up the mess in Indian Academia in an instant. Indian academia needs to seek a transformation from within,” IRW declares in its X bio.

Indian scholarship is coming under increased scrutiny at a time when a plagiarism controversy has engulfed American academia after the controversial exit of Claudia Gay, the first black woman president of Harvard University. In the last two decades, groups such as Retraction Watch and Center for Open Science and Data Colada have been calling out bad research, according to a New York Times article. But Indian academic publishing has existed in a grey zone of lax rigour and a cottage industry of fake journals. For too long this has gone unchallenged.

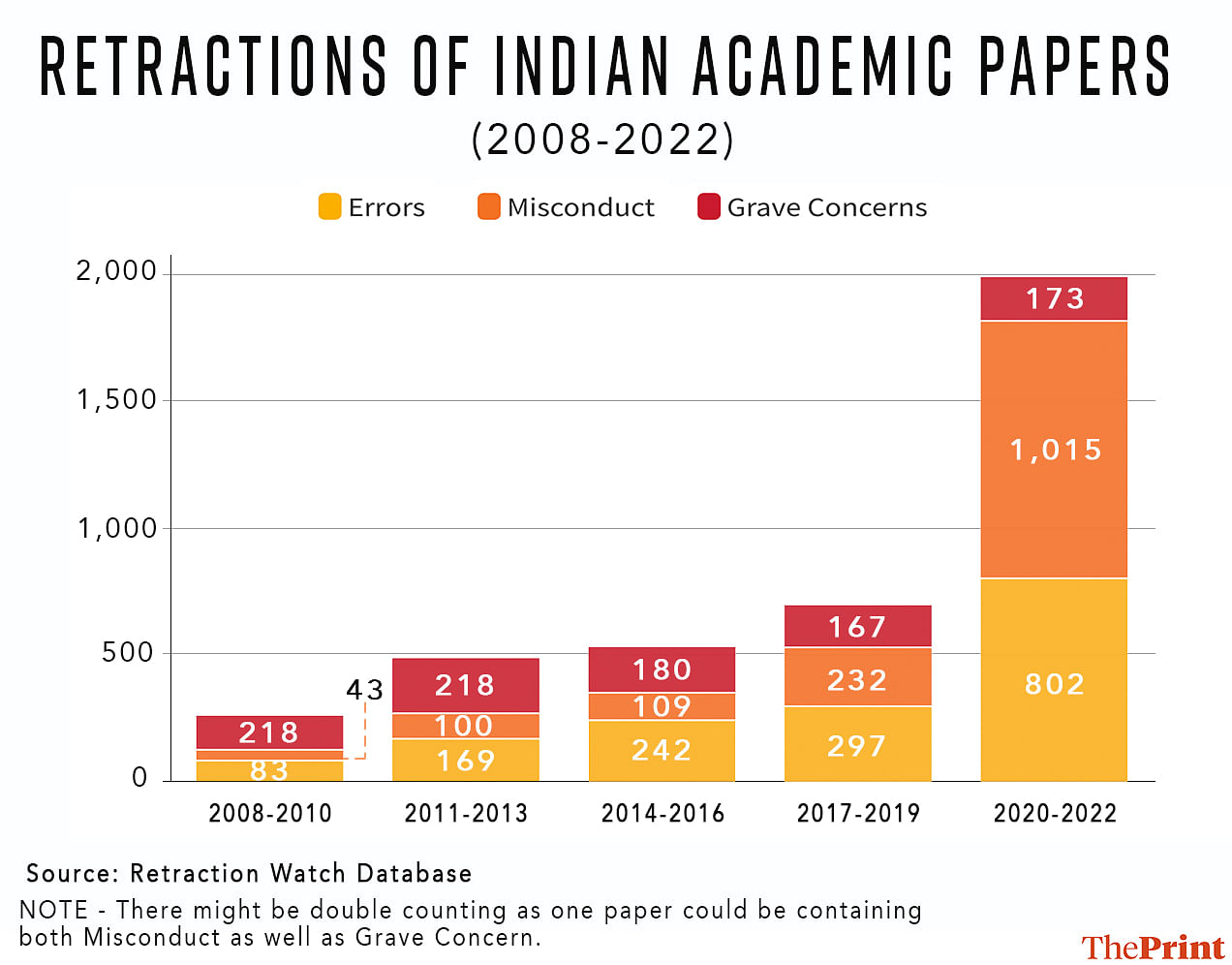

By 2022, India had become the third largest producer of scientific research, overtaking the UK. At the same time, the number of retractions also rose dramatically. According to IRW founder, Achal Agrawal, retractions from India increased 2.5 times between 2020-2022 over the number recorded between 2017 and 2019. Fifty-eight papers by 12 top Indian Institutes of Technology were retracted between 2006 and 2023 for plagiarism and duplication.

But the new watchdog is set to change the business-as-usual. And its members are not afraid to get their hands dirty. Their goal is an academia that is held accountable for plagiarism, data manipulation, bogus publications, and fudged citation metrics among other academic ‘sins’. Since it was founded in 2022, the group has been actively calling out researchers and top scientific institutes on X and LinkedIn.

It flags dubious studies, names and shames researchers who churn out hundreds of bogus papers every year and calls out universities that it alleges encourage unethical means to increase their overall rankings.

This will fill a gap in the Indian research environment, where it is often the case that unethical behaviour is not called out or acted upon

– Gautam Menon, professor, Ashoka University

Plagiarism, image manipulation, paid publishing, paper mills and ghostwriting in academia is an open secret, yet there is silence from within the community. Indian universities are nowhere near the panic situation that has been sweeping American campuses in the past month. Not just Harvard; MIT and Stanford were also under scrutiny.

“It is risky for professors and academics to speak up about it because then there might be harm to your career,” said Agrawal. His analysis also revealed that top research institutes are among those with the most number of plagiarised research papers.

Last year saw the highest number of retractions globally, with more than 100,000 retractions. Sleuths around the world have found instances of papers that have been written with rewriting tools like ‘Quillbot’ that generate nonsensical phrases in an attempt to skirt plagiarism detection software. And there’s a thriving paper mill industry even in India where academic research papers are ghostwritten and published for a price.

Agrawal realised that Indian academia was in dire need of a watchdog when he learnt that one of his first-year undergraduate students had published a research paper that was completely plagiarised.

“This student told me that he had published a research paper. I was surprised—because he could not even solve my assignments. I asked him how he wrote a paper,” said Agrawal. Much to his surprise, the student said that publishing was easy – he had simply taken another research paper, paraphrased it and submitted it.

“I asked him if he knew this was plagiarism. He said, ‘No, no it isn’t plagiarism, it passed the plagiarism test software’,” he said. This conversation helped him realise how deep-rooted the problem was. The lack of transparency means that researchers with several dubious publications are often appointed to prestigious institutions because they are evaluated on publication metrics and citation indices.

“It is actually affecting the education system,” said Agrawal.

Stolen papers

This war against unethical research is also playing out on Pubpeer, a US-based platform that allows people to flag issues with research papers after they have been published. Through the platform, several papers by Dhanraj Gopi, a chemistry professor at Periyar University in Tamil Nadu, were flagged starting in 2019 for image duplications. Of these seven were retracted by the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) in the UK.

In some cases, the retractions are not prompted by watchdogs, but by researchers whose work has been stolen. In 2019, Amit Kapoor* found that his paper—published in 2016 as a master’s student at IIT-BHU—had been plagiarised and published in 15 papers by another researcher.

“They had picked up parts of the graphics in my paper [and used it] in their own research papers,” said Kapoor, who specialises in tribology—an interdisciplinary field which studies the science of friction, wear, and lubrication.

After much back and forth with the journals, Kapoor was able to get nine papers retracted. Two others had been published in the reputed Elsevier journal, Fuel. Kapoor approached then-principal editor Jillian Goldfarb in an attempt to get the papers retracted.

“Goldfarb was very helpful. But even after six months of trying to follow up with the editor-in-chief of Fuel to take those articles down, nothing worked,” he said.

Incidentally, in October last year, Goldfarb resigned from her post citing, among other things, the journal’s ethics team not taking any action on ‘dozens of papers’ with ‘serious concerns about paper milling’. Despite all this, Kapoor said that the researcher who plagiarised his paper is now working at a reputed Indian university.

Most top institutions in India have outlined research ethics guidelines. At the Indian Institute of Science, an inquiry committee can be set up to take action in cases of research misconduct. However, the institute declined to comment on its process and cases when ThePrint reached out. Similarly, the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, in 2019, issued a notification on ethics of research—a 22-page list of guidelines on falsification, fabrication, fraud and other forms of misconduct.

A senior CISR official, who did not wish to be named, told ThePrint that when cases of misconduct at the institute were highlighted, action was taken against the researcher through an internal enquiry. However, such information is not publicly shared. Those within the close-knit circle of academia are often aware of the black sheep. But the public in general, and potential future employers, are often in the dark.

Several scientists who have been called out by PubPeer have obtained directorial appointments in top academic institutions during the last five to six years

– Ayan Banerjee, IISER Kolkata

There are exceptions—the rare occasion when an institute steps up to accept responsibility and seek accountability. In 2021, the National Centre for Biological Sciences ensured that the developments regarding a case of research misconduct were promptly relayed to the public. The paper, ‘Discovery of iron-sensing bacterial riboswitches’ drew the attention of many readers on PubPeer. The academic ethics committee of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) launched an inquiry and found evidence of image manipulation and result falsification. But such transparency is rare, which is what compelled Agrawal to create IRW.

Academic whistleblowers

Agrawal didn’t always set out to be an academic vigilante. He began by informing institutions and following due process. But it did not go far. The response just did not have the sense of alarm that he had expected.

“Initially, when we started we would first inform the author and the university before posting publicly. We would give them a deadline to respond,” Agrawal said.

But that process would take two to three months with rarely any tangible outcome. “Sometimes we have to flag on social media because without doing that, there is no response,” he said.

IRW has a public portal, where anyone can act as a whistleblower—exposing papers that may have been published by unethical means. “We also have a Discord group where researchers and academics actively consult each other and act on these tips,” he added. The organisation has over a hundred members, with new volunteers regularly joining in. But everyone has a pseudonym.

Members discuss the merits of cases of misconduct and launch coordinated efforts to identify repeat offenders. The group is regularly buzzing with new ideas and projects. The team is now working on creating a graphic dashboard on their website that can help anyone track retraction data. Some share screenshots of ads on social media that put papers up for sale so that everyone can track when such papers appear in journals.

Sometimes we have to flag on social media because without doing that, there is no response

– IRW founder Achal Agrawal

Most of the group members are from academia and are driven by a shared frustration of having to compete for jobs and promotions with people who follow unethical means to get published.

“We judge the tips on the merit and verifiability of the claims,” said Agrawal. But in the absence of transparency and communication by the institutes themselves, the worry is that platforms like IRW can be used by fellow academics to settle personal scores.

Anindita Bhadra, a researcher at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Kolkata draws attention to how competitive the academic world can get where the emphasis is on publishing first.

“If one gets called out for their work, they need to prove the allegations wrong. That takes time, and they lose out,” said Bhadra. This makes it very necessary for platforms like IRW to make sure they have enough proof before posting allegations.

As a safeguard, IRW is careful not to name anyone who may be at the start of their academic career. “We name people and universities who are publishing dubious articles to win awards and rankings,” said Agrawal.

The race to publish

What Agrawal wants is to raise awareness to lead to an overhaul in the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) rankings. It was adopted by the Ministry of Education in 2015 to rank universities and colleges and enable students to compare them. But over the years it has been criticised as flawed and prone to data fudging.

It also triggered a race among institutes to increase the number of publications. In this publish-or-perish listing race, many university administrators are pushing their faculty to bring out more papers.

“Most people agree that the pressure to publish is because of NIRF rankings,” said Agrawal. IRW alleges that since NIRF was introduced in 2015, retractions from India have gone up fourfold.

I think many are uncomfortable with this. They feel that someone can be targeted by rivals. The way I see it is, if you are honest, you don’t need to worry

-Anindita Bhadra, IISER Kolkata

In 2023, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Chennai, was ranked first under NIFR’s dental college category, but the same year, it also came under the scrutiny of Retraction Watch for an alleged mass-scale self-citation scheme. ‘Did a ‘nasty’ publishing scheme help an Indian dental school win high rankings?” was the investigative report, published in Science magazine.

“While the National Assessment and Accreditation Council gives due weightage to publications in UGC-Care listed journals, the NIRF uses publication data only from Scopus and Web of Science,” read an op-ed piece in The Hindu by GS Bajpai, vice-chancellor of the Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab.

Often, NIRF rankings of the top 50 state universities are not in keeping with NAAC scores. Bajpai concluded that “severe methodological and structural issues” undermine the ranking system.

Naming and shaming

The frustration regarding the sheer volume of bogus papers from India has been brewing for years, but now academics agree that the time has come to name and shame researchers on social media.

“Right now, this will fill a gap in the Indian research environment, where it is often the case that unethical behaviour is not called out or acted upon,” said Gautam Menon, professor of physics and biology at Ashoka University. But transparency even among self-appointed watchdogs is important.

“To be credible, they should be willing to feature responses to allegations from those accused and also set high standards for publicising potential ethical issues in research,” he added.

Many scientists are hesitant to openly point out flaws in a peer’s published paper, for fear that it will invite retribution when their research comes out.

“I think many are uncomfortable with this,” said Bhadra, referring to the idea of platforms calling out people on social media over the integrity of their research. “They feel that someone can be targeted by rivals. The way I see it is, if you are honest, you don’t need to worry.”

The exercise of peer review itself is a highly subjective exercise. Every research paper is reviewed by two or three researchers from the same field before it gets published. When scrutinising published papers, especially those that came out more than a decade ago, it’s important to be sensitive to the technology timeline, says Alka Rao, a researcher at CSIR—Institute Of Microbial Technology (IMTECH).

“We must not apply high-resolution technology of today in retrospect to hang people for data concluded in the past using low-resolution tools,” she said.

That said, Rao agrees that factual errors must still be highlighted to safeguard against persisting and systematic errors originating in past faulty data sets.

Ayan Banerjee from IISER Kolkata is far more sceptical about what is plaguing the academia currently. He sees a massive difference between the perception of the community by those within it and by the political or bureaucratic ‘leadership’ of the country.

“Several scientists who have been called out by PubPeer have obtained directorial appointments in top academic institutions during the last five to six years,” Banerjee said.

“So does it really matter what the academic community feels about unethical work in this country of ours?”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

News Related-

Anurag Kashyap unveils teaser of ‘Kastoori’

-

Shehar Lakhot: Meet The Intriguing Characters Of The Upcoming Noir Crime Drama

-

Watch: 'My name is VVS Laxman...': When Ishan Kishan gave wrong answers to right questions

-

Tennis-Sabalenka, Rybakina to open new season in Brisbane

-

Sikandar Raza Makes History For Zimbabwe With Hattrick A Day After Punjab Kings Retain Him- WATCH

-

Delayed Barapullah work yet to begin despite land transfer

-

Army called in to help in tunnel rescue operation

-

FIR against Redbird aviation school for non-cooperation, obstructing DGCA officials in probe

-

IPL 2024 Auction: Why Gujarat Titans allowed Hardik Pandya to join Mumbai Indians? GT explain

-

From puff sleeves to sustainable designs: Top 5 bridal fashion trends redefining elegance and style for brides-to-be

-

The Judge behind China's financial reckoning

-

Arshdeep Singh & Axar Patel Out, Avesh Khan & Washington Sundar IN? India's Likely Playing XI For 3rd T20I

-

Horoscope Today, November 28, 2023: Check here Astrological prediction for all zodiac signs

-

'Gurdwaras are...': US Sikh body on Indian envoy's heckling by Khalistani backers