No One Is Prepared for a New Era of Global Migration

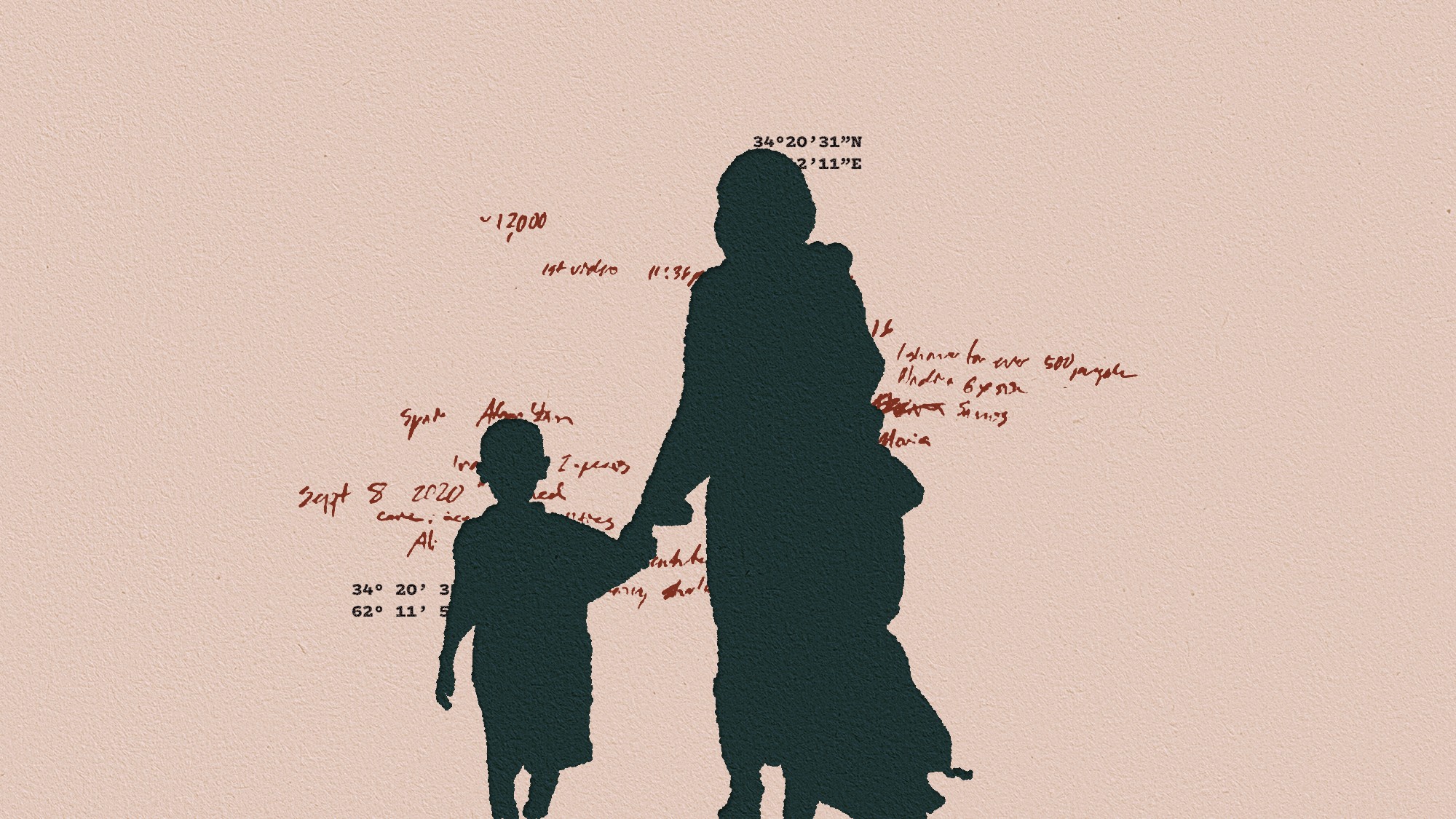

On the evening of September 8, 2020, the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos erupted in flames. The inferno was exacerbated by the camp’s close quarters and shoddy construction. As Lauren Markham writes in her new book, A Map of Future Ruins: On Borders and Belonging, the fire sent thousands of refugees from countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq fleeing “to an empty stretch of road with no reliable food or water or medical care or bathrooms.” No one seemed to know how it started; it could easily have been an accident. But soon after, Greek authorities accused six young Afghan camp residents of setting the fire, and arrested them. (Markham writes that while reporting on the incident, she could find no “real evidence” that they were guilty.)

Markham’s book is about the contemporary migration crisis. As of 2022, some 100 million people around the world have fled war, persecution, and instability in their home countries for uncertain futures in others. She could have written an excellent book based on the Moria fire alone, one that reconstructs the Afghan refugees’ lives, examines what compelled them to take such a perilous journey to Europe, investigates the conditions under which Greece constructed a dilapidated camp, and details the injustices of the legal trial that followed the fire. Most migration stories carry with them tremendous drama, as Markham knows well. Her first book, The Far Away Brothers, was a work of immersive reportage about two teenagers’ journey from El Salvador to the United States, and the lives they subsequently built in California.

But soon after the Moria scene, Markham signals that her second book will be different. She has traveled to Greece not only to report on the fire but to discover the history of her own Greek family, who arrived in the United States more than a century ago. Markham believes that attitudes toward migration often contain an element of contradiction—for instance, when some Americans see their own family’s immigrant background as a source of pride, while at the same time rejecting the right of others to, similarly, make a new life in a new country. She suggests that by identifying and exposing hypocrisies like these, prejudice against migrants might also fall away.

[Read: ‘Welcome to Europe. Now go home.’]

Markham’s pivot from straight reportage to this more literary, inquisitive mode might be familiar to journalists who have covered intractable political or economic problems and come to question the point of their vocation. Reporters can serve the public by revealing abuses of power and the failures of society and state to protect the vulnerable. In doing so, they hope that society will improve. But after years spent writing about borders, Markham is skeptical about her ability to change anything, and seems to think that a mix of reporting, history, and memoir might make a more profound impact on her readers’ ability to identify with migrants’ humanity. Although Markham’s searching narrative can be thought-provoking, the personal elements of her book don’t always shed much light on the migrant crisis today, as enormous and complex as it is.

The story of the six Afghans on trial provides a thread that runs through Markham’s book—and is its strongest element. She focuses on Ali, a young migrant who left Afghanistan when he was 13 years old, believing he’d be able to find a better job and life in Europe. Markham offers a worthy recounting of the period from 2015, when many Greeks showed empathy to refugees, primarily Syrians fleeing the civil war, to Moria camp’s degeneration in the years leading up to the fire. Her description of life at Moria, and especially the night of the fire, through Ali’s eyes, is a feat of reconstructive reportage, poetically written: “This was smoke, but nothing like the smell of a cook fire or a woodpile burning; it was the stench of human things on fire, things that weren’t meant to burn.” The twists and turns in Ali’s trial reveal how a young refugee accused of a crime in a foreign country has little recourse, and Markham does a great service in exposing the shadowy, punitive systems he faced.

Interspersed between the Moria passages are sections of memoir, primarily accounts of Markham’s visits to Greece as a Greek American reporter and tourist. On Lesbos, she explores Greek communities that had been forced to migrate during the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923, wherein Greek residents of Turkey were removed to Greece and Muslims in Greece were transferred to Turkey. On Andros, the island from which her family originated, she attempts to understand the circumstances that led to her ancestors’ migration to the United States. Andros offers few such clues, but she persists in her line of inquiry. “On the surface, my family’s story has nothing to do with Ali’s … nothing to do anymore, even, with Greece,” she admits. But she doesn’t think people can “reckon with the injustices of contemporary migration” without learning about past migrations.

Markham’s probing and at times murky explorations sometimes seem to be the point of the book. Halfway through, she pauses to explain her own struggle with journalism as a means for telling important stories about migration. Conventional reportage feels constrictive to her, unable to contain the enormity of the subject. She argues, for example, that journalism can fail to portray refugees as people with agency rather than victims of larger forces. She also notes that news and magazine stories about migration are often dominated by linear accounts, in which a migrant flees desperate conditions and either triumphantly attains refuge or is cruelly denied it.

[Read: America’s immigration reckoning has arrived]

Markham wants journalists to resist these expectations and tell stories that challenge familiar narratives. It’s an intriguing idea: Upended narratives might force people to question common assumptions about migration, to identify creative solutions they have not yet thought of and cast off pieties to which they cling. But Markham’s story emphasizes moral failings, both individual and political, leaving readers wondering about the practical, logistical complexities of the current crisis, such as whether any country has enough hospitals, shelter, and schools for the growing numbers of migrants, or the capacity and willingness to offer reasonable pathways to citizenship. Markham’s laudable impulse to encourage personal introspection begins to feel inadequate compared with the magnitude of the problem. In 2021, a Gallup poll found that about 900 million people globally said that they wished to migrate. Erasing prejudice alone won’t solve the migration crisis; these numbers demand new international institutions, similar to those founded after World War II, to manage the coming era.

In recent years, migration has steadily become a more complicated and unpredictable issue. For instance, migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border often don’t come from just Latin America but from places as far-flung as China or Turkey. Four years before the Moria fire, in an attempt to relieve the Aegean and Mediterranean border crisis, the European Union struck a deal with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In exchange for 6 billion euros, Erdoğan promised to keep refugees who had arrived in Turkey and were hoping to continue onto Europe, in the country. Some people thought that Muslim-majority Turkey was a better place than most countries in Europe for a Muslim refugee population, and for a while that seemed true. But they didn’t realize that a deep anti-Arab racism lurked within the country, and by the time the Turkish economy began to collapse around 2018, many Turks took out their fury on the ubiquitous newcomers. By March 2023, when I last visited, refugees weren’t the only ones who dreamt of leaving Turkey; young Turkish men spoke of saving for a ticket to Mexico and crossing the U.S. border, something I had never heard in my 16 years reporting in that country.

Markham argues that expanding and complicating the most typical migrant narratives will help us “co-construct new, less ruinous storylines, new forms of belonging beyond borders.” But her discovery of her own family’s history doesn’t yield insight on how to do so. While reading A Map of Future Ruins, I was reminded of one of my journalism students, who is himself Afghan. Looking up from some magazine articles I had assigned—ones that melded memoir with explanatory reporting—he said angrily: “What is the point of these magazine stories?” He believed journalism was supposed to say what happened, what mistakes were made and by whom, and what needs to be fixed. Many young people I’ve talked with, anxious about their own fate, long for writing that doesn’t necessarily offer tangible solutions but at least provides hard, factual fodder for them. They look for damning and fulsome descriptions of the cruel and inadequate systems they are navigating, and a glimpse of what’s needed for their fast-arriving future. Markham shouldn’t lose faith in her reportorial powers—there will be many millions more people in need of the close attention of journalists like her.

News Related-

Russian court extends detention of Wall Street Journal reporter Gershkovich until end of January

-

Russian court extends detention of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, arrested on espionage charges

-

Israel's economy recovered from previous wars with Hamas, but this one might go longer, hit harder

-

Stock market today: Asian shares mixed ahead of US consumer confidence and price data

-

EXCLUSIVE: ‘Sister Wives' star Christine Brown says her kids' happy marriages inspired her leave Kody Brown

-

NBA fans roast Clippers for losing to Nuggets without Jokic, Murray, Gordon

-

Panthers-Senators brawl ends in 10-minute penalty for all players on ice

-

CNBC Daily Open: Is record Black Friday sales spike a false dawn?

-

Freed Israeli hostage describes deteriorating conditions while being held by Hamas

-

High stakes and glitz mark the vote in Paris for the 2030 World Expo host

-

Biden’s unworkable nursing rule will harm seniors

-

Jalen Hurts: We did what we needed to do when it mattered the most

-

LeBron James takes NBA all-time minutes lead in career-worst loss

-

Vikings' Kevin O'Connell to evaluate Josh Dobbs, path forward at QB